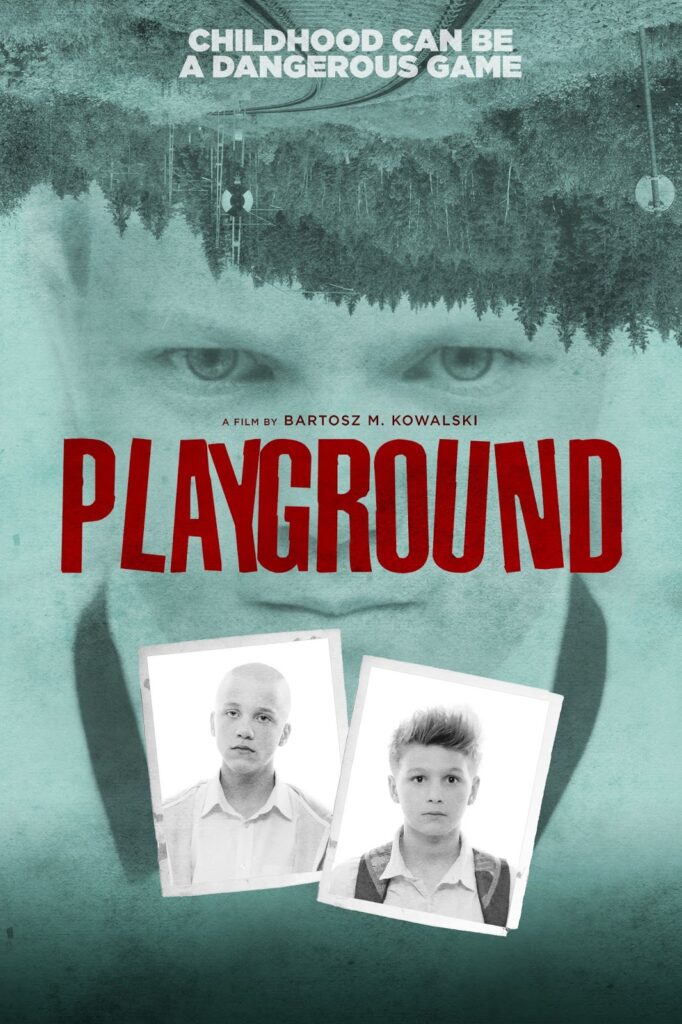

PLAYGROUND (a.k.a. Plac Zabaw) ***** Poland 2016 Dir: Bartosz M Kowalski 82 mins

Documentarian Kowalski makes his feature film debut with PLAYGROUND, a devastating translation of an infamous British murder case to 21st century Poland. The UK media’s exploitative, rabble-rousing coverage of this horrifying crime is in direct opposition to Kowalski’s intelligent, understated approach, which, for about an hour, operates as a realistic study of the routine cruelty inherent in the mundane existence of three Year 6 children.

The adolescents are from disparate backgrounds : Gabrysia (Michalina Swistun) comes from an affluent, barely present family and her unhappiness is immediately apparent; Szymek (Nicolas Pryzgoda) lives in a high rise with the extra responsibility of assisting his disabled dad; and Czarek (Przemek Balinksi) hails from a tenement slum. The unpopular, overweight Gabrysia plans to confess her love for Szymek, blissfully unaware that the boys can’t even remember her real name, referring to her only as “Fatty”. The lives of the three students intersect on the last day of school before the summer break.

Befitting his background, Kowalski’s film unfolds entirely via handheld cameras, and in all-natural light, adopting an unnervingly voyeuristic tendency to literally follow its protagonists, as if eavesdropping on their conversations and everyday lives. Small but significant details – kids burning insects with a magnifying glass in the school playground, a character tormenting a stray, starving dog – prove portents for far greater misdemeanours to come, as do the various early moments captured from a distance, some literally from behind closed doors. Adults are either absent or entirely ineffectual: the film captures an assembly full of children universally disengaged by the meaningless advice trotted out by the Principal. The focus is entirely on the alarmingly authentic, unaffected trio of performances by the young actors.

The single time Kowalski drastically departs from his clinical, observational style is in the penultimate chapter, “Ruins”, where typical schoolyard insults (“retard”, “slut”) escalate into a prolonged of all too credible adolescent male cruelty, captured (and replayed) on a cell phone. Unfolding via an anxious series of jump cuts, close-ups and urgent camerawork, it is among cinema’s most realistic depictions of bullying. Nothing, however, prepares the viewer for the sunlit horror of the final act: unfolding in near-silence and in one audacious, utterly harrowing nine minute take from a considerable distance, its scarring impact is only heightened by the chilling tableau of its aftermath. Kowalski offers no definitive explanation for the behaviour we have seen, nor does he offer any hope for the future of anyone involved. His message is that any attempt to explain or rationalise such unthinkable behaviour is only ever speculative and, thus, of minimal use or relevance. The film, however, is among the boldest of the movies brave enough to accept the capacity for savagery in children, and its harshest lesson reminds us how adult society isn’t equipped to either deal with its aftermath or prevent its repetition.

Review by Steven West