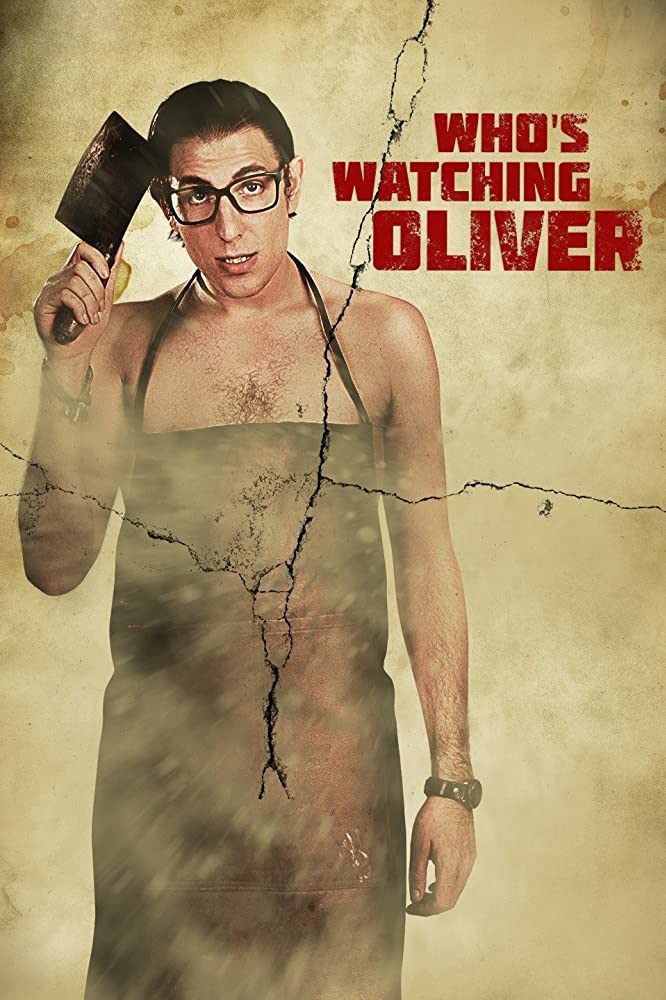

WHO’S WATCHING OLIVER *** USA / Thailand 2017 Dir: Richie Moore. 92 mins

The feature directorial debut for Richie Moore – co-written by star Russell Geoffrey Banks – explores the grim territory of post-PSYCHO character studies about American psychos. It flirts with MANIAC’s most improbable element by following the budding romance between the physically repulsive Oliver (Banks) and a beautiful American girl (Sara Malakul Lane) though replaces the grimy domestic backdrop of films like DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE with an ironically colourful, multi-cultural Thai setting. Oliver is one of modern horror’s socially inept Mummy’s boys: gawky and bespectacled with slicked-back hair, sensible trousers and a love of jazz music and cats. If you hang around him long enough, he has a jarringly manic laugh and delivers a set of pre-rehearsed chat-up lines as if he were Michael Caine’s hitherto unknown, unbalanced little brother. His life is controlled by a foul mouthed, alcoholic Irish mother (Margaret Roche), played to the hilt as a monstrous exaggeration of the off-camera Mrs Bates and with a strong dose of the matriarch from 1980’s MOTHER’S DAY. Under her command, he picks up young women so he can rape and kill them while she enjoys the show via his webcam. Veering from pitiful, puny geek to alarming brute in the blink of an eye, Banks’ fearless portrayal of Oliver is truly startling. The childhood abuse he suffered (as in DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE) is conveyed partly via the comic-strip he creates in a failed bid to exorcise his demons. A typical evening involves him being coerced into wanking for his mum’s pleasure. Early on, the film appears to be heading toward full-blown “extreme” horror territory (in the vein of THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE II), but its horrifying initial rape-murder cheered on by “Mumma” (“stick it in her smelly arse!”) proves to be the only truly explicit sequence in the movie. The solace Oliver finds in Sophia (Lane) strives to generate empathy for the alienated protagonist, though a sense of dread informs the whole picture, reinforced by harrowing scenes of his descent into hysteria. Less assured is the attempt to shift from jet black humour to outright rage at ruined lives such as Oliver’s – an imbalance reflected by the offer of two very different outcomes at the end (one of which, as is annoyingly common, after the credits).

The feature directorial debut for Richie Moore – co-written by star Russell Geoffrey Banks – explores the grim territory of post-PSYCHO character studies about American psychos. It flirts with MANIAC’s most improbable element by following the budding romance between the physically repulsive Oliver (Banks) and a beautiful American girl (Sara Malakul Lane) though replaces the grimy domestic backdrop of films like DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE with an ironically colourful, multi-cultural Thai setting. Oliver is one of modern horror’s socially inept Mummy’s boys: gawky and bespectacled with slicked-back hair, sensible trousers and a love of jazz music and cats. If you hang around him long enough, he has a jarringly manic laugh and delivers a set of pre-rehearsed chat-up lines as if he were Michael Caine’s hitherto unknown, unbalanced little brother. His life is controlled by a foul mouthed, alcoholic Irish mother (Margaret Roche), played to the hilt as a monstrous exaggeration of the off-camera Mrs Bates and with a strong dose of the matriarch from 1980’s MOTHER’S DAY. Under her command, he picks up young women so he can rape and kill them while she enjoys the show via his webcam. Veering from pitiful, puny geek to alarming brute in the blink of an eye, Banks’ fearless portrayal of Oliver is truly startling. The childhood abuse he suffered (as in DON’T GO IN THE HOUSE) is conveyed partly via the comic-strip he creates in a failed bid to exorcise his demons. A typical evening involves him being coerced into wanking for his mum’s pleasure. Early on, the film appears to be heading toward full-blown “extreme” horror territory (in the vein of THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE II), but its horrifying initial rape-murder cheered on by “Mumma” (“stick it in her smelly arse!”) proves to be the only truly explicit sequence in the movie. The solace Oliver finds in Sophia (Lane) strives to generate empathy for the alienated protagonist, though a sense of dread informs the whole picture, reinforced by harrowing scenes of his descent into hysteria. Less assured is the attempt to shift from jet black humour to outright rage at ruined lives such as Oliver’s – an imbalance reflected by the offer of two very different outcomes at the end (one of which, as is annoyingly common, after the credits).

Review by Steven West